Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

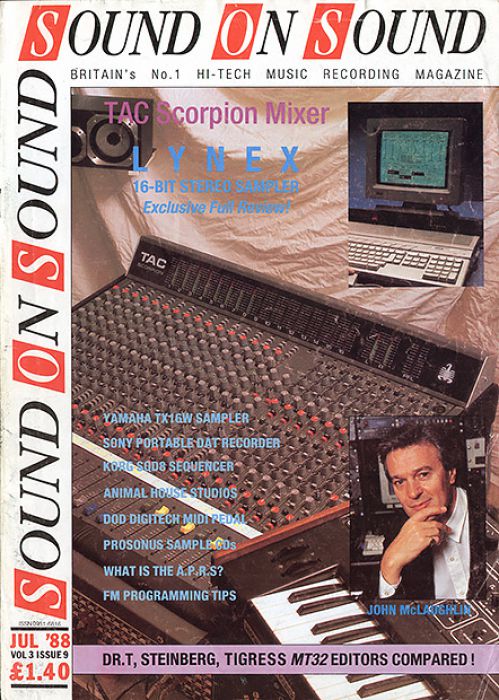

Yamaha TX16W Sampler | |

Article from Sound On Sound, July 1988 | |

All good things come to those who wait... David Mellor samples Yamaha's version of the 'ultimate instrument', the MIDI sampler. Does it improve on all that have gone before or have Yamaha taken technology beyond the point of usability?

David Mellor samples Yamaha’s version of the ‘ultimate instrument’, the MIDI sampler. Does it improve on all that have gone before or have Yamaha taken technology beyond the point of usability?

Although the TX16W is Yamaha's first MIDI sampling module, it is not their first foray into the professional sampling field. Their range of PCM drum machines shows that they already have the technology to store sounds digitally for replay on command. It may be one or two steps up the technological ladder to make an instrument that can play a sample at several pitches simultaneously, and to add all the other bells and whistles that the well-dressed sampling module needs these days, but Yamaha have shown time and again that they have the ability to compete in the forefront of musical innovation. They were first with FM for the working musician. They may well be among the last to join the ranks of the sampled digits, but they can be certain that a lot of people will still be interested in what they have to offer.

The obvious next question is, just what can they offer? A sampler is just a device for getting real sounds to respond to a MIDI keyboard, surely? Can it be judged purely on its bit-quotient and memory capacity? Or perhaps a sampler needs a unique feature of some sort to differentiate it from others in the same price range.

The Roland S550, for example, has the unique feature of its partnering video monitor, which compares to an LCD display like Frank Bruno to an amateur featherweight. Yamaha's unique feature is a system of digital filtering. In fact, the full name of the TX16W is a Digital Wave Filtering Sampler or Echantillonneur a Filtrage de Donnees Numerique, if you'll pardon my French. Rather than the more usual variable top-cut filter, Yamaha have employed a series of digitally-implemented equalisers which may be statically and dynamically altered. It certainly sounds interesting on paper, but more of that later.

Something rather more important than the digital filter is the actual sound of the machine. 'The sound of a sampler?', you ask. Yes, different samplers do sound different. Everyone knows that synths sound different, but with samplers that seems rather more unlikely.

My first serious encounter with MIDI samplers was a hired Prophet 2000. Not too easy to operate, but it had a damned good sound. I could never figure out why I couldn't get the same kind of sound from my Akai S900. I just couldn't get the 'presence' that the 2000 had. I still don't know the answer, obviously something to do with the digital workings, but as soon as I played the Yamaha I knew what I had been missing since those Prophet 2000 days. I should say now that it's a subjective matter, and you may not like the bright sound of the TX16W - less 'realistic' you might think. I would recommend auditioning the Yamaha unit against either the Akai S900 or the Roland S550, taking identical samples on each and playing them back at different pitches. You will hear a difference, and you'll know straight away which machine you prefer. Soundwise, I'll go for the Yammy.

SPECS

You won't need specs to see that the TX16W has a lot of what it takes to be big in the sampling world. A 1.5 megabyte memory for one thing, 16-note polyphony for another - not forgetting stereo sampling, and mixed and individual outputs on the back. It puzzles me sometimes why samplers are specified in terms of megabytes instead of their maximum sampling time. Perhaps one and a half million bytes is supposed to sound more impressive?

The sampling time available at 33.3kHz sampling rate is 22 seconds, according to my experiments. Not that you can take a sample this long, unfortunately. The longest continuous chunk of sound you can record is 7.9 seconds at this sampling rate, or 16.3 seconds at 16.7kHz. A sampling rate of 16kHz, remember, means an audio bandwidth of less than 8kHz. Considering that one of the major uses of samplers is to 'touch up' recorded vocals, I prefer the S900's ability to sample at 12kHz audio bandwidth for up to 15.8 seconds. 12kHz is adequate for vocals, 8kHz usually isn't.

Although the TX16W may be short(ish) on maximum continuous sampling time, it obviously isn't on total time available. And seeing that the memory is expandable up to six megabytes, you could have a hell of a lot of performing power in there all at once. Don't expect to fit six megabytes onto one floppy disk though! Two DSDD 3.5 inch disks are needed to fill the unexpanded TX16W's hungry belly.

As is common with many instruments, the operating system of the TX16W must be loaded anew from disk each time you switch on. The usual warnings regarding losing/damaging the disk, and buying the unit expecting the system to be updated to include further features that you want, apply. There is a function for copying the system disk, so sensible users will have no problems in making a backup copy. The TX16W is a fully functioning system already, so I wouldn't imagine anything more than minor changes via updates. Yamaha may not forgive me for mentioning that it takes one and three-quarter minutes to load the operating system and the digital filter tables before you can do anything. In comparison, the Akai S900 (which has its operating system in ROM with updates supplied on disk) is ready to go in seven seconds.

Other matters which are worth mentioning, spec-wise, include the TX16W's maximum sampling rate of 50kHz. One could say that since Compact Disc only has a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz that this is overkill, but if you think that transposing the sample down a couple of octaves reduces the rate to 12.5kHz - and the audio bandwidth to around 6kHz - then I could think of applications where you need all the initial bandwidth you can get.

Stereo sampling is an important feature too. Sometimes I do it with my mono-only sampler, with a lot of fiddling around. However, once you have made up the necessary lead for the TX16W (it's a stereo jack on the front panel) stereo sampling is as simple as mono. And if I mention that the maximum sampling time is still 7.9 seconds (at 33.3kHz), the same as mono, then you'll want to pat Yamaha on the back too. Stereo sampling should, in my opinion, be included on any serious machine from now on.

STRUCTURE

If I keep referring to the Akai S900 it's (a) because I have one, (b) because it's a damned good machine. The manual I got with mine, back in 1986, was a bit nonexistent, but I was up and running with it in no time. The S900 has two variables to play with: the sample and the program. The sample is what it says, the program is the way samples are treated and mapped onto the keyboard.

Yamaha, for reasons of their own, have chosen to have five variables. Phew! It's a lot for the simple mind to cope with, but if you like the sound of the machine then cope with it you will. Apparently, Yamaha UK are producing a simple English version of the manual to better explain how to get started. I hope it has some sort of tutorial section so that you can follow through step-by-step the procedure from sampling to performance. It's a lot to handle.

The five variables of the TX16W are:

• WAVE - the truncated and looped sample

• FILTER - a digital filter setting

• TIMBRE - the Wave with Filter, LFO and envelope settings

• VOICE - an arrangement of Timbres across the keyboard

• PERFORMANCE - a combination of Voices

As you can see, the opportunities for complication are inherent. Hopefully, as the various parameters and procedures are explained, all will become clear.

Sampling mode is entered by pressing the Sample key. That's straightforward enough. The TX16W's backlit display then presents you with a short menu: Frequency, Level and Record. 'Frequency' is where you set the sampling rate and the expected length of the sample. The available rates are, as I mentioned earlier, 50kHz mono, 33.3kHz mono, 33.3kHz stereo and 16.7kHz mono. The sample length is set in blocks, where each block is just under two milliseconds (at 33.3kHz sampling rate). This is a clear example of complication for its own sake. You have to enter the time in blocks, but you are immediately given the equivalent in milliseconds. So you quickly learn how many blocks make a second, but why not enter the length directly in milliseconds? There is no advantage to the way it's done here.

Available sample triggering options are Auto, Yes Key, Foot Switch, External, Input-Foot, and Ext-Foot. 'Input-Foot' obviously means that you have to give the machine a kick to start it off! Seriously, it means that if the footswitch is pressed, and the level of the signal coming in exceeds the triggering threshold, then sampling will start. 'External' is where a trigger signal must be applied to the front panel Ext Trig jack socket. A fairly versatile series of options, but no 'Previous' function like on the Roland S550 and S330, where the sound already in the memory is held when a key is pressed - useful for sampling words or phrases from old films on the TV, as is the current trend.

In Sample Record mode, there is a bargraph display of signal level together with a threshold indicator. Two oddities appear here. Firstly, the threshold level for auto-triggering is strangely unalterable. I would have thought this was essential. Sampling sounds with a slow attack phase has to be done here by manual triggering instead. Secondly, although an indication of clipping (distortion) is given before sampling begins, there is no indication of peak level whilst the sample is being taken. Result: you don't know that you have overdriven the input until you replay the sample. Strange.

The Wave Edit function has seven menu items. Before I go on, I must explain something else that seems odd to me. The TX16W has things called 'Edit Buffers'. With sample editing, the sample has to be entered into the buffer memory before it can be altered in anyway, ie. truncated or looped. You cannot work directly on samples which are in the section of memory normally accessed from the MIDI keyboard. This is okay while you are taking new samples, because samples are placed directly into the buffer memory as you take them. After editing, they are copied to the normal memory - 'Internal Memory' as Yamaha call it. But... remember when I said that the memory capacity of the TX16W is 1.5 megabytes? That memory has to serve both internal memory and buffer memory. Total memory capacity is 22 seconds at 33.3kHz bandwidth, but that is spread between the two memory areas. If the internal memory is full you can't copy anything to the buffer memory. If the buffer is full, vice versa. Once again, this does nothing but complicate matters. I found that I had to keep erasing samples and swapping them around to do all the editing I wanted. It also means that you can't actually fill the entire 22 seconds of internal memory by sampling alone. There would always be a little bit left in the buffer that you couldn't transfer because there wasn't the space to make a copy. You can, thankfully, use the entire internal memory capacity when loading sounds from disk. I just don't see the benefit of the buffer. If it's meant to be there as some sort of backup - well, isn't that what disks are for?

Having got that off my chest, the Wave editing functions are as easy to use as you would wish. There is a nice 'normalising' feature which brings samples recorded at too low a level up to full strength - not helping the signal-to-noise ratio of course, but a handy function nonetheless. Looping is also a straightforward matter. Not as good as the Roland S550 where you hear alterations to the loop as you make them, making it very quick to find good loop points. On the TX16W, you have to play the note again to hear the change. Once you have set up rough loop points, the TX's Autoloop function can be brought into play. A sniff better than the S900's autoloop I would say. There are also a selection of Crossfade Loop, Reverse, and Sample Mix functions. When the sample is edited to complete satisfaction, it may be named if you wish.

DIGITAL FILTERS

The filters of the TX16W are all digitally implemented in real time. Not like the Akai S900, where the filter is analogue, or the Roland S550, where the filter is digital but does not work in real time (ie. filtering as you play). The benefits would seem to be that the noise ought to be lower and the variety of filter shapes more versatile.

Figure 1. Graph showing the Notch Filter (Frequency 3kHz-5.5kHz, Level 0dB-30dB). One of 16 possible filter types available on the TX16W sampler.

The system disk supplied with the TX16W contains 16 different basic filter shapes. Yamaha call them 'tables', but this seems rather confusing to me so I'll stick to the way I can best explain them. Figure 1 shows one of the filter shapes, which is a fairly typical example. This is a notch filter with two variable parameters - the centre frequency of the notch, and the depth of the notch. All the filters have two variable parameters. Most have frequency, which corresponds to the notch's centre frequency here, and level, which corresponds to notch depth in this case. A few of the filters offer frequency and the slope of the filter as the two variables.

In use, one of the two variable parameters can be statically controlled. That means you set it when you edit the filter and it stays set. The other parameter can be dynamically controlled via the filter's envelope generator and LFO, or by MIDI controllers such as modulation wheel, breath controller etc.

So far, it seems that there is a wide choice in the way you can filter a sampled sound. What you probably want to know is what the filters sound like. The best description I can think of is 'subtle'. You are not going to get the sound of a swept analogue filter from them, but then again, you probably wouldn't want to use such an old-fashioned sound anyway. They do make quite a nice effect, but don't be too impressed by how many filters there are and the degree of control that seems to be available. All I could achieve was, as I said, quite a nice effect. Nothing extraordinary, in fact a lot of the time I was hard-pushed to render any audible effect from them at all. The programmer of the supplied factory sample disks obviously had the same trouble...

'Voice Edit' covers not only the creation of a voice (terminology explained above) but the creation of a Timbre. Only the keyboard split facility affects the Voice as such, everything else affects Timbres directly. Voice Edit at its basic level concerns how the various Timbres are spread across the keyboard. Each Voice may have up to 32 Timbres active, each with its own keyboard slot which may not directly overlap, but it is possible to crossfade between Timbres in adjacent slots over a range of one to nine notes. This is a useful feature for evening up the differences between multiple samples of the same instrument. Other Voice Editing functions are covered in a separate panel.

'Performance Edit' is all about combining a number of Voices. Here, you can layer sounds together or have them appear on different audio outputs. You may be surprised to learn in this day and age that notes are not assigned to Voices automatically by the TX16W. For example, you may have a sequencer playing different Voices on different MIDI channels. But before making any music you have to decide how many notes you want each Voice to be able to play. There is no dynamic voice allocation, whether from the mixed audio outputs or from the eight individual output sockets. The Akai S900 gives you 8-note dynamic allocation from its mono output, and 4-note dynamic allocation from each of its stereo outputs. The Roland S550 (and S330) gives you full dynamic allocation - or manual allocation if you wish.

The TX16W has a number of other interesting functions which are unusual and potentially useful, such as Velocity Curve, which sets the degree of response of the unit to MIDI velocity messages - including the ability to play softer as velocity increases. Also, Velocity Bias allows you to alter MIDI velocity after a note has been played. That's an interesting concept! And it works.

DISKS

It's not usual for the subject of floppy disks to receive its own separate heading, but this time it is deserved. I mentioned earlier that it takes a considerable period of time to load the operating system from disk. It also takes quite a time to load sample disks too. As much as 1 minute 45 seconds for one disk. This is a long time by any standards and the waiting is a source of great frustration.

Another problem, not unique to Yamaha, is the difficulty of loading several Performances from different disks into the memory. Perhaps this has to do with the way samples are identified within the machine? On the Akai S900, each sample is given a name. In fact, it must be given a name because this is the only means of identifying it. With Yamaha's system (and Roland's too), there is a numbered slot in memory for each sample. Sample names are only there for user convenience.

So what does this mean? Well, you might load one Performance from a disk, say, which uses samples placed in slots 1, 2 and 3. If you wanted to load another Performance into the memory simultaneously, from another disk, it might also want to use the samples in slots 1, 2 and 3. There is an obvious incompatibility here, so you would have to load a Performance, load the necessary Voices, and then load samples into the correct locations individually. The S900's system avoids this completely, because samples can go into the internal memory wherever the operating system pleases, a sample's name is its tag. You can load ten or more programs (the equivalent of Yamaha's Performance) from ten different disks, with a minimum of button pushes and no brainwork, as long as the total sample time doesn't go over the limit. It really is a much better way of doing it.

VIEWPOINT

SPECIFICATION

- Polyphony: 16 note

- Key splits: 32

- Sampling rates: 50kHz mono, 33.3kHz mono, 33.3kHz stereo, 16.7kHz mono

- Resolution: 12-bit

- Total sampling time: 22 seconds at 33.3kHz

- Max sample length: 5.2 seconds (50kHz), 7.9 seconds (33.3kHz), 16.3 seconds (16.7kHz)

- Audio inputs: stereo jack

- Audio outputs: 2 Mix jack outputs, 8 individual outputs, stereo headphones

- Storage: 3.5" DSDD floppy disk

- Display: 40-character illuminated LCD

The Yamaha TX16W is something of a puzzle. To me, it is a really great sounding sampler and I certainly wouldn't mind having a machine like this to complement my Akai S900. The problem is that it is not easy to use, and so slow to load disks.

Some people regarded the DX7 as difficult, but it wasn't really. It just had a lot of functions to control, and it controlled them pretty well. In the case of the TX16W, there is perhaps a little more to cope with than in the average sampling module, but not that much. If Yamaha are to help buyers to learn how to use the TX16W quickly, and to explore its full potential, then a better manual is essential.

Price £1999 inc VAT.

Contact Yamaha-Kemble UK, (Contact Details).

TX16W MENU OPTIONS

SYSTEM SET-UP

MASTER VOLUME: Sets the level for mixed outputs I and II, individually or simultaneously.MASTER TUNING: Sets overall tuning for the TX16W, variable over +/- one semitone.

MIDI SWITCH: Specified MIDI messages can be acted upon or ignored according to settings made here: Program Change, Control Change, Aftertouch, Pitch Bend, Note-on, Note-off. (The last two refer to the TX16W's ability to respond to either all MIDI note numbers, even numbers only or odd numbers only. In this way, two TX16W's can be chained to produce 32-note polyphony.

CONTROL NUMBER ASSIGN: MIDI Control Change messages can be reassigned to different controller numbers.

PROGRAM CHANGE: This determines how MIDI Program Change messages select different Performance numbers.

DEVICE NUMBER: Sets the device number on which the TX16W will receive MIDI System Exclusive messages.

PROTECT: When on, data cannot be stored into the TX16W, nor can bulk data be accepted via MIDI. As sample data is held in volatile memory, this does not guard against power failure.

PERFORMANCE EDIT

VOICE ASSIGN: Selects the number of notes available to each Voice in the Performance.RECEIVE CHANNEL/ALTERNATE ASSIGN: Determines the MIDI channel for each Voice. Notes can also alternate between Voices.

OUTPUT ASSIGN: Sets which audio output each Voice goes to.

VOLUME: Sets the level of each Voice.

DETUNE: Each Voice can be detuned independently.

PERFORMANCE LFO: Sets the parameters of the Low Frequency Oscillator that will apply to all the Voices in a Performance.

MIDI NOTE SHIFT: Incoming notes can be transposed two octaves up or down.

EXTERNAL TRIGGER: A footswitch or an audio input can trigger a specified note.

PERFORMANCE NAME: 20-character name.

VOICE EDIT

SLOT: Sets the arrangement of Timbres across the keyboard.WAVE ASSIGN: Assigns a particular Wave to a Timbre.

FILTER ASSIGN: Assigns a Filter shape to a Timbre.

PITCH: Gives independent tuning for each Timbre in a Voice.

VELOCITY CURVE: A six-parameter curve can be programmed for each Timbre - including the ability for a Timbre to play softer as you play the keyboard harder.

AMPLITUDE EG: Determines how the level of a Timbre varies over time. High notes have shorter envelopes than low notes.

PITCH EG: Determines how the pitch of a Timbre varies over time, over a range of eight octaves (but within the maximum transposition range of a sample).

LFO: Separate Low Frequency Oscillator settings for each Timbre in a Voice.

AMPLITUDE MODULATION SENSITIVITY: Sets the MIDI controller (Mod Wheel, Aftertouch etc.) which will determine the amount of amplitude modulation.

PITCH MODULATION SENSITIVITY: Similar to the above, but for pitch.

VELOCITY BIAS SENSITIVITY: Allows MIDI controllers to increase the MIDI velocity after a note has been played.

PITCH BEND: Sets the range of the pitch bend controller.

TIMBRE NAME: 10-character name.

FILTER EDIT

TABLE: Sets the basic curve of the filter from a selection of 16 supplied on the system disk.FILTER EG: Determines how the effect of the filter will vary over time.

FILTER LFO: Separate LFO for the filter.

KEY SCALING: Filter settings can be varied over the length of the keyboard.

LFO MOD SENSE: Determines how MIDI controllers (Modulation wheel. Aftertouch etc.) affect the LFO.

BIAS SENSITIVITY: Determines how MIDI controllers affect the filter.

FILTER NAME: 10-character name.

WAVE EDIT

LOAD TO BUFFER: Places a Wave in the area of memory in which it may be altered.TRIM: Sets the start and end points of the Wave.

LOOP: Sets the loop points of the Wave.

LOOP CROSSFADE: Sets a fade time to smooth over the join at the loop point.

REVERSE: Can set various parts of the Wave to play backwards.

MIX: Mixes two samples which were loaded as a pair.

WAVE NAME: 8-character name.

SAMPLE

FREQUENCY: Sets sampling rate, sample length, record trigger options.LEVEL SET: Adjusts the level of the incoming audio to be sampled.

RECORD: Arms the sampling process.

UTILITY

STORE: Transfers memory from the edit buffer to the internal memory.DISK LOAD: Loads following from disk; Filter Table data, Wave data, Voice and Timbre data, Performance data, or the entire memory of the TX16W.

DISK SAVE: Saves data to disk.

FORMAT: Formats disk or saves operating system to disk.

INIT: Initialises data in the edit buffers.

DISK COPY: Copies the whole of one disk to another disk.

MIDI DUMP: Transmits bulk data. The TX16W sends and receives System Exclusive messages for front panel switches, parameter changes, and various bulk data types. Wave data may be transmitted as bulk data according to the MIDI Sample Dump format.

Also featuring gear in this article

Publisher: Sound On Sound - SOS Publications Ltd.

The contents of this magazine are re-published here with the kind permission of SOS Publications Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Review by David Mellor

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for March 2025

Please note: Our yearly hosting fees are due every March, so monetary donations are especially appreciated to help meet this cost. Thank you for your support!

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £18.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!